Intro

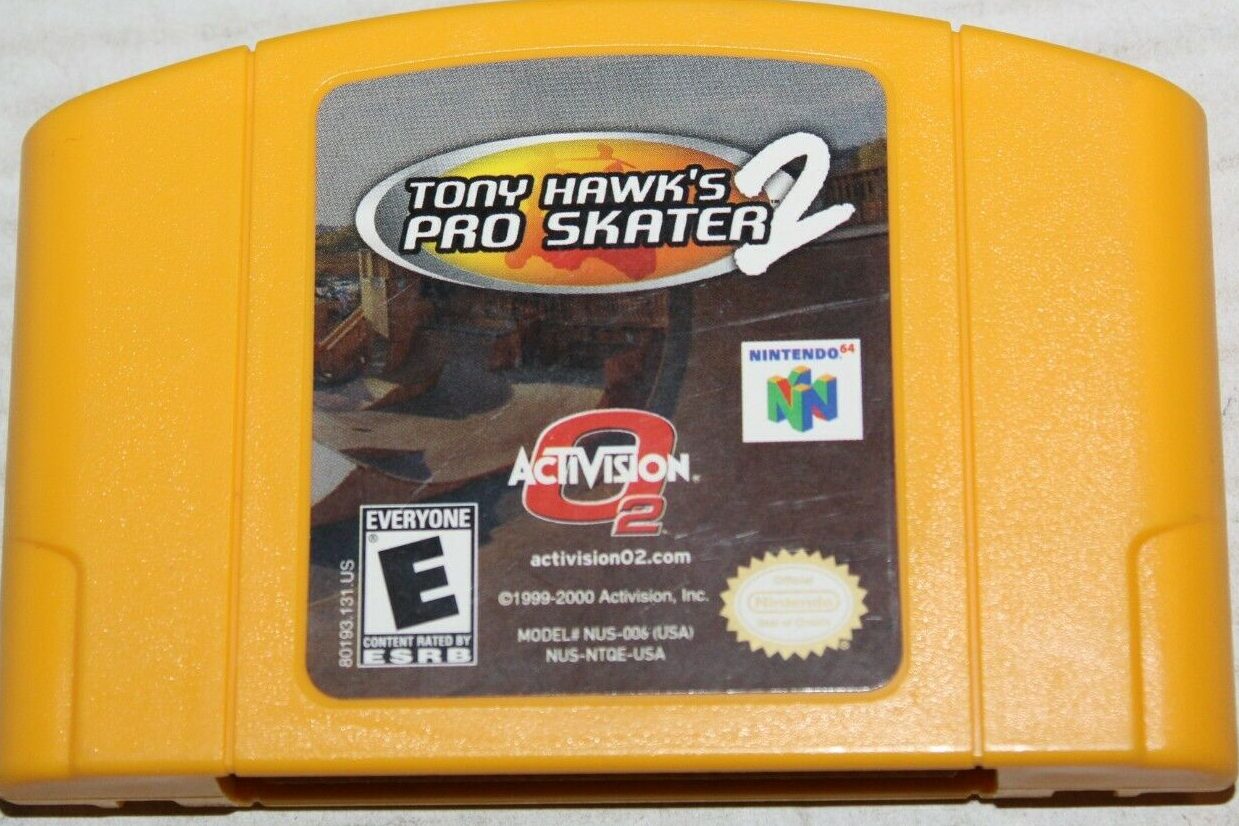

The new video game “Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 1 + 2” was released for PlayStation 4 at the beginning of September 2020. The new game re-releases two video games I spent countless hours enjoying – “Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater” (1999) and “Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2” (2000).

| Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, 1999 | Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2, 2000 |

When the games were first released I was 14 years old – near the peak of my video gaming years and these games exerted profound influence on me by partially pushing me to learn to skateboard, which I continue to enjoy to this day, almost 21 years later.

| Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2x, 2001 | Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater HD, 2012 | Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 1+ 2, 2020 |

Seeing pre-release footage of the new game gave me a sinking feeling but putting word to my intuition came with tremendous difficulty. There were questions: When you have a new game that is essentially two games stuck together, is it better? What if the new version has state of the art graphics and they seem to look better than the state of the art graphics from 21 years ago? What if they changed something that you really liked about the game, like what the up button does, are they allowed to do that? What are relevant ways to compare ‘editions’ of the same game? Have I become an old curmudgeon that is desperately clinging to my childhood treasures?

I intend here not to review this new game (I still haven’t played it – I will follow up with a review) but to unpack how I feel about it from the outside and discuss what I think are some relevant points to consider about reproduction art. This essay details my thought process on unravelling the answers to these questions. There are three sections: some thoughts about how remakes can be judged aesthetically, a quick discussion of video-games, and discussion of the Tony Hawk’s franchise and surface-level gut-check.

A Basis for Judgement

To have an opinion we must judge and to judge we must have a basis from which to do so.

Before diving directly into the specifics of video games, we need to ask how one judges a ‘re-release’ or adaptation? How does this kind of judgement differ from judging a work that is wholly new? Where bounds the realm of re-publishing?

Hardly something unique to video games or even ‘new’ in any sense of the word transcribing a work from one medium to another goes back approximately as far back as does recorded history. The transcription of the epic sumerian poem Gilgamesh from the oral form into written word on clay tablets in ~2,000BC serves as a great example.

It is important to judge how much fidelity the reproduction or new edition has to the original. For instance, if a book is republished with many words from the original missing then it is a poor copy.

However, if the most important aspect, the essence, of the first work is captured then perhaps there is some room to play with the other less important parts of the work as when the setting and period of a story are changed to better suit a particular audience while the characters and their relationships stay remain more or less the same.

| Athena – Greek Originals | Athena – Roman copies of Greek Statuary | Athena – American copy of something [link] |

A Platonist, someone who staunchly agrees with the aesthetic theory of the 4th century BC ancient Athenian philosopher, might snub the whole enterprise of ‘reproduction’ on the basis that art, properly so called, is a copy from or of nature and, regardless of its fidelity, a copy of a copy is just one step further away from truth.

Reproduction is in this way regarded in the same light as the children’s game of ‘telephone’ where one child starts with a word or sentence and whispers it into the next child’s ear. That child whispers it to the next and so on. Inevitably, the word or phrase is mangled beyond recognition once it reaches the last child in the chain.

In contrast, a video game or other artwork may be created simultaneously on several platforms or mediums and the ‘original’ can be purely virtual and may not be manifested objectively: each version of the original draws from the same prototype to reproduce its essence (with more or less fidelity).

Fidelity

Fidelity is how exactly a reproduction matches its source material. When an artist creates an original artwork the fidelity looks inward only to the intentions of the artist.

If the artist intends to recreate in oil paint the luster of the plumage of a Mallard, then the fidelity can be judged by how well the painting illustrates the artist’s impression of a Mallard and how well the artist’s impression of a Mallard mirrors our own.

When the work is republished or remade the judgement of fidelity is made in respect to the source material, so one dimension of judgement is along how accurate and precise the new edition replicates the original work.

Transcribing

The art of transcribing is the art of attempting to evoke the ‘essence’ of a work within the boundaries of another not-entirely-similar medium. Most commonly, transcribing refers to the translation of text from one language to another or from an older form of language to a newer form.

Transcribing can also take a work of writing or artwork across mediums that are characteristically different. Some musicians base their songs on books, some authors base their books on songs, and some painters base their paintings on Operas. Some architecture is based on pastries.

| Arcade Original, 1980 | Atari 2600, 1982 | Famicom, 1984 | Game Gear, 1991 | Nintendo 64, 1999 | PS2, 2005 | PS3 Xbox360, 2014 | iOS, 2020 |

Transcription is an important aspect of modern, widely-released video games (and thus the judgement of such). For a variety of reasons (but especially because video games are such a new medium) there isn’t a single, long-standing platform for which they are built, and, as such, the developers commonly transcribe them for or between systems that they work with. Often, developers must ‘convert’ an old video game for it to work on new video game systems

In video games the labor of transcribing ranges in difficulty from changing a few parameters to completely rewriting and rewiring the product from scratch. It is so common that industry termed the practice: ‘porting’. A video game originally made for one system, say, Xbox, gets ‘ported’ to another, say, GameCube. Entire teams and even whole studios specialize in porting video games from one console over to another. Many video game publishers port their games across systems to increase the number of people that can purchase and play the game.

| Betamax | CED Videodisc | Widescreen Director’s Cut Laserdisc | Laserdisc |

| VHS Widescreen, director’s cut | DVD | HD DVD | Bluray |

Much like video games, transcribing was the norm in film and movies from at least 1975-2015. Studios would shoot a movie and release a photographic celluloid-film video reel which was intended to be viewed in a movie theater. Another version would be released later in commodity copy form for home viewing on television sets on mediums such as magnetic tape, video disc, or as a pure digital data. The commodity/consumer version was necessarily heavily altered in form as well as in content: advertisements were added ahead of the movie, and often the aspect ratio was changed to better match that of normal television screens.

One final note, for an artwork made with or otherwise composed of decaying and disintegrating matter, such as sand, chalk, paint, wood stone, or digital memory bits, transcription is vitally important for the work to continue to exist beyond when the original copies finally succumb to the elements

Essence

Essence is the most highly perfected and most important element or elements of a work of art. It is at the core of the experience. The strongest emotions, sentiments, or senses that are evoked from a work of art. The essence is the single sentence or single line summary of a work. The essence is the succinctly distilled finest points of a work.

Essence appears differently to different people with different capacities for judgement. A carpenter and a chicken farmer might both see a framed painting of a tropical parrot and see very different things. The carpenter might see the shoddily constructed frame as part of the essence, the farmer might think that the exotic bird was the most essential part, while the artist may have intended a timely and pointed cultural reference to be the most important aspect of the work.

Evolution in form perhaps shows essence the best. In the evolution of THPS we see through the many titles in the series that the essence is:

- A fast-paced challenging and interactive experience

- A loosely realistic/superhuman depiction of skateboarding

- A taxonomy of connectable, point-generating character tricks

- A fantastical version of the world in which almost every surface can be skateboarded upon and tricks can be performed

Re-makes handily tend to improve, damage, or tune the essence of the work they attempt to recreate. By definition they differ in an identifiable way from the source material and the differences will tend to measurably change, enhance, or degrade the essence of the original version. This represents a means by which artwork can evolve as it is reproduced.

If a work is popular enough it will tend to be reproduced. When works are reproduced they are introduced into the public consciousness and become representative. Works that become well known then get reproduced themselves.

Artworks have some chance of being reproduced by a given viewer and are experienced or thought about over time by a varying rate of people. The chance of being reproduced by a given viewer is a quantity that relates to how moving the work is to them and how likely they are to remember the work.

| Novel, 1897 | Silent film, 1922 | Remake, 1979 | Shadow of the Vampire, 2000 | What We Do In the Shadows, 2015 |

There are some great examples in the horror genre of this. One is Nosferatu, a 1922 visually striking German silent film based on the 1897 Irish horror novel ‘Dracula’. In 1979, a film remake of ‘Nosferatu’ was made which clearly attempts to recreate the essence of the German film, especially the striking visage of the title character, instead of deriving directly from the principle work, Dracula. Nosferatu evolved the essence of the story and is now itself a work worth recreating for its own sake. In other words, Nosferatu is a species of vampire now distinct from Dracula.

When transcribing a work there may be trade-offs required in terms of its essence. For instance, when translating written poetry judgements need to be made between changing the text to match meaning, rhyme, and meter; it is rare to directly match all three across languages all of the time.

Video game media

It is important to denote a few things about video games – what they are and how they have existed in time so that their relationship to the world is more clear.

Video games are automatic, interactive video and or audio experiences in which one or more players attempt to accomplish an uncertain goal.

Video & Audio output

The way a player can gauge their progress through the video game is through feedback delivered by video and audio cues. In new, advanced graphic video games, this may appear as photorealistic passage through a fantasy world replete with hyper-accurate physically-simulated audio synthesis, but games can conceivably be as simple as flickering lights and buzzers.

The video and audio is a designer-curated torrent of art given to the player as a time-sequence of visuals and sounds.

Input

| Xbox One | Oculus Quest | Dance Pad | WiiMote | Atari Joystick |

The player controls the uncertain conclusion in a video game by somehow using real-world objects to manipulate the game world. For example: almost all video game consoles have physical, hand-held controllers that allow the player’s fingers to press buttons and push and pull joysticks, some games use the physical location of the player in the world to control the game, and games can also interpret sound, such as spoken word, to guide the game.

Rules & Goals

A video game must have rules and goals. The goals and the rules function as the virtual referee and officiate the experience and eliminate debate about how the game is and or should be played. For instance, the game might give points to the player that clearly indicate what in-game actions bring them closer to the goal.

Rules and goals can also be emergent meaning that a player may also play a game along a subset rules and or goals which they decide themselves, as in a scrabble game where one player decides to play only words that are somehow related to the ocean, or plays her words to build an interesting shape.

The goal of the game is the solution; the rules define the possible routes to get there.

A video game without a goal is without a way to win or lose and is only an interactive experience; a video game without rules cannot be circumscribed well enough to be contained in a system.

Story & Design

Game design is the way the rules have been contrived to create the player’s experience of the game. Game design covers many topics.

- It ushers the player through learning the rules and controlling the game.

- It structures the relative difficulty of progression towards the goal throughout the gaming experience.

- It realizes the visual ‘look’, the audible sound, the pacing, and the emotional environment

The story can be either internal or emergent. A video game such based on the real-world sport of soccer, may not have much if any story embedded within the goal – for instance, two players may simply have to follow the simulation’s virtual soccer-rules to compete at the goal of getting more points than the other player’s team in a defined period of time. In this case the story is emergent and emerges as the details of the players’ competition; it is defined only by the rules of the game and consists of the gameplay as remembered by the players.

The game may have a narrative: perhaps the game evokes the dreams of a rising soccer star who needs to prove his worth to his family the only way he ever imagined: winning the hometown soccer tournament. In this case, although the player still can weave their personal story through the game, a story scaffold is present and guides the player’s narrative.

History

Video games started as distractions for intrepid and creative university staff and students that had the opportunity to hang out around early computers which were huge, slow, expensive, and rare. It wasn’t until the early 1970’s that computers began to get cheap enough for individual consumers to afford that video games started to appear for them. The computerized arcade game market flashed into existence and computer-game arcade cabinets started becoming popular at the very same time in both the USA and Japan.

In an effort to market games, developers have consistently attempted to be sensational; improving development techniques and increasing quality. This race pushed and drove the frontiers of computer graphics outward from the 1970’s to present day. Every new video game greedily uses as many resources as it has available to it in order to show more images, faster, in more colors, and more realistically in order to stand out from the crowded fields of games that cannot create as much magic with the same hardware power. Every new game system promises more memory storage, faster internet connection, higher audio fidelity, and the ability to show more detailed graphics on screen.

Alongside the ever increasing power of the hardware in which these games run the possible scale of development has drastically increased as well. In the earliest days most video games were created by development teams that were usually under 10 people. The programming, art, design, business, testing, and marketing were done by these small teams. The financial returns from the overall video game industry has grown steadily as the medium has matured and definitively eclipsed those of the movie industry in 2009 with the cross-platform release of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2.

These huge sums of money have allowed the specialization of roles and the expansion of teams and growth of publishers. Video games have become amongst the most widely distributed popular cultural commodities in post-industrial nations. The teams that create them can span from hundreds to over a thousand individual contributors.

Games developed in these environments are enormous undertakings that have extremely high production value. They are widely distributed, are extremely well tested for faults and problems, and have ultra-high production value. They contain highly refined stories and design, well-tuned and balanced gameplay, and unbelievable technological feats.

As hardware capabilities have expanded fewer restrictions have burdened game developers. As more developers push out into the frontiers many genres and themes have emerged.

When internet access reached a saturation point multiplayer online games that wouldn’t have been compelling without hundreds of players became worthwhile.

Themes in video games evolve and reference one another in addition to works in other mediums. Zombies, a rapidly evolving horror film antagonist, became super popular in the late 2000’s and early 2010’s.

When consumer-available hardware matured sufficiently 3D video games became realizable and suddenly entirely new game types such as 1st person shooters proliferated.

In 2020 video games seem ubiquitous: anyone can play them on cell-phones, personal computers, in web-browsers, in arcades, on handhelds and consoles, and inside of other video games.

- Video game hardware and especially the quality of graphics continues to get better

- The upper limit of video game production value continues to go up

- Thematic fads and trends continue to evolve and change

- Game developers continue to face difficult decisions about which platforms/hardware to support as the market remains spread thin.

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater was first released when skateboarding was still a fairly young sport (having only been invented in the 1960’s in the USA). Riding a cultural rollercoaster, it had become a widespread phenomenon by the early 1980’s only to precipitate out of consciousness by the mid 1990’s. Tony Hawk was among the last cadre of the ‘celebrity’ skaters to come of age in the 1980’s and in 1999 was an aging 31 year old (now 52) in a acrobatic sport dominated by young men under 25 when he landed his sensational, nationally televised 900 degree aerial spin in the xGames three months prior to the release of the game.

Punk and Ska music similarly experienced a golden age with hugely popular bands like No Doubt, Sublime, Green Day and Blink 182 taking some of the musical attitudes to wider audiences and leaving people ready to dig deeper into their respective genres.

Video games were rapidly evolving in 1999. The 5th generation console, the Sony PlayStation, was released in 1995 and was capitalizing on the growing popularity of “3D” polygon graphics – a huge step forward from the two dimensional worlds that dominated video games from their start in the 1960’s through the first half of the 1990’s. There were few standard precedents to build off of in terms of control styles and 3D graphics – many games had to reinvent how to move things through space and how to give the player a good view of the world to play in while trying to make it look as plausibly real as they could.

The THPS series landed perfectly in 1999 to catch the swelling resurgent wave of skateboarding in America in the late 1990’s. When the games were first released they were considered to have good graphics, excellent control and design, and unmatched soundtracks. The games sold extremely well and have left a long legacy.

But what made them so great? Was it the music? The graphics? The sales? Did it just get lucky with its release timing? Did it capture the essence of the late 90’s? Is there some golden kernel of video gaming, or indeed, of the human spirit held within?

A Pre-Judgement

(I will follow up this article with an actual review of THPS1+2 for PS4)

After watching the videos of the demonstration version made available prior to release of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 1+ 2 and using the criteria painstakingly laid out above, which is admittedly far shy of actually enjoying the experience of playing the game, and at the risk of sounding overly biased and afraid of change I can say that this new game is, in fact, not a recreation of the original, it is the drawn out reverb of an echo of 1999’s sound and fury. The game doesn’t seem to be trying at all to reproduce the original in the dimensions of either look or gameplay.

Is Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 1+ 2 reaching out to grasp at the design and aesthetic ideals which the first editions of THPS and THPS 2 only failed to reach because of the limitations of the then-current generation of consoles? Or because so many changes have been made are we not to understand this as a copy? Is the game just a distantly related set of game mechanics still using approximations of the old designs?

When THPS is viewed from the perspective of a series, it can partly be seen as progressive refinements and experiments developing and honing the design, art, technology, and controls of the first game to better suit and delight the players. As evolution then, the essence of THPS 1 and 2 can be seen as a negative space – a hole – what do these two games lack that is present in later renditions in the series in terms of controls, graphics, and gameplay/goals and rules? The developer filled many of the ‘holes’ in by re-vitalizing the graphics and using the later era mechanics. The introduction of these elements results in a poor reproduction as far as fidelity to the originals is concerned.

In my opinion, as far as gameplay was considered, the degree of combo-connectedness was perfect in THPS2, thus all of the additional, running, wall-plants, reverts, skitching etc become irritating noise drowning out the sweet, sweet musical balance of a “kickflip -> manual -> crooked-grind -> nose-manual -> boneless -> hardflip -> 540 benihana” line combo. The presence of these new elements is therefore, in addition to being a poor copy of the first version, a nuisance.

The inspiration for the game becomes very confusing – the game seems to take mechanics from the whole of the series, the music and level lay-out from the first two games, offers some changes on top of that (such as completely revamped graphics and new playable characters), and even though it is published by the same entity, Activision, it was not made by the same development team, Neversoft, disbanded long ago.

As far as fidelity is concerned, the new game is a long stride of departure from the first two games in the series in terms of appearances, sound, content, and gameplay, which is to say that it has very low fidelity to the source. The graphic detail has been greatly increased such that it feels contemporary alongside modern PlayStation 4 games. Several songs have been removed from the soundtracks of the original games. New playable skaters have been added and some sponsors (and their in-game decals) have been changed or removed. The trick system is very different. Everything has been re-created from scratch.

A skeptical, pessimistic take is that the new game is simply the publisher’s way of making an edition available on new game systems while including veneer of 2020 ‘relevance’ on the top (new/different graphics, music, and playable characters) that will serve well to keep the memory of the series alive. It could also be a litmus test to see how well prepared the world is for more arcade-style skateboarding video games.

If the game were a novel then I surely would not be interested in purchasing a new edition of a book that I already own a copy of and enjoy. Even if it had a fancy new dust jacket, a new character in the story, and new, advanced adjectives that provide more descriptive detail of the action… But in the case of THPS 2, although I have a cartridge for Nintendo 64 and an Nintendo 64 on which it can be played, the game console isn’t what it used to be – it doesn’t always turn on, the audio and video connectors are becoming antiquated and worn out, and I no longer live close to any friends to play multiplayer with them on a system with no capability of internet play. A new edition that works on a still-supported video game console, with network play is enticing; especially as I have disposable cash with which to pay for caricatures of my fondly remembered nostalgia.

| THPS, 1999 | THPS2x, 2001 |

| THPS HD, 2012 | THPS 1+2, 2020 |

It is easy to be more than a little bit puzzled about how to understand this release. The fact that in the 21 years since the originals were released there are three complete-game remakes featuring both THPS 1 and 2 available immediately suggests that these games (Tony hawk 2x, Tony Hawk HD, Tony Hawk 1+2) ought to be cross-compared with one another gauge their respective merit as they are all trying to do the same thing – copy the original.

For fans of the two games such as myself I am so thoroughly filled with mixed feelings. On the one hand I demand an exact replica of the games I loved so dearly – no changes! the same graphics! Ever the contrarian perfectionist, I demand the exact same gameplay and controls! But I shall not have it – it will be vaguely reminiscent in appearance of the shapes of the old levels with a recreation of controls from much later on in the series. But on the other hand what joy and vindication! O! To be able to relive the joys of these old games again, the satisfaction of once again being able to revisit times gone by with old friends who were there with us way back then and at the same time be able to have an ancient, yet freshly-polished jewel to proudly show anew to those of us who weren’t yet there to see it the first time around!

As each video game and video game console sinks deeper and deeper into the collective cultural detritus and fewer originals remain working in the open and out of landfills we can only hope that something remains of these once big hit wonders, if not for archaeology and anthropolgy’s sake then for the joy that they are to play, read, and write.

Bibliography & Further Reading

“History of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater (1999 – 2015)” THPS documentary on youtube

‘HIGH SCORE‘ video game documentary on Netflix – [preview]

The Art of Game Design : a Book of Lenses by Jesse Schell [link]

The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction – Walter Benjamin [wiki]

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 on metacritic [link]

Discussion of the 2019 Resident Evil 2 remake on Camouflaj Radio Tape 57 – [link]

Many thanks to those who graced me with their time to edit and critique my thoughts <3. -Ben